USDT Tracing report

07/24/19 05:48:48 AM UTC

Foreword

This document is prepared with pandoc markdown, and available in the following formats:

You can read the epub with a browser extension such as epubreader for chrome, or epubreader for firefox. The epub is the most enjoyable to read, the PDF is more academically formatted, and the html is meant for broad accessibility. Enjoy!

This document is an open-source report on Userspace Statically Defined Tracepoints (USDT). The document source is available on github. If you find any errors or omissions, please file an issue or submit a pull request. It is meant to be a useful manual, with reference implementations and runnable examples. It will also explain how USDT probes work on linux end-to-end, and demonstrate some practical applications of them.

This is intended audience of this work is performance engineers, who wish to familiarize themselves with USDT tracing in both development (assuming Mac OS, Linux, or any platform that supports Vagrant, or Docker on a hypervisor with a new enough kernel), and production (assuming Linux, with kernel 4.14 or greater, ideally 4.18 or greater) environments.

Disclaimer

The following demonstrates the abilities of unreleased and in some cases unmerged branches, so some of it may be subject to change.

The following pull requests are assumed merged in your local development environment:

- Support for writing ELF notes to a memfd backed file descriptor in libstapsdt for storing ELF notes in a memory-backed file, to avoid having to clean up elf blobs accumulating in

/tmpdirectory when a probed program exits uncleanly. Presently UNMERGED, but is used byruby-static-tracingby default and will probably be the default forlibstapsdtafter some rework. This is only an issue if you find the need to buildlibstapsdtyourself, and want to use memory-backed file descriptors. - Build ubuntu images and use them by default in kubectl trace for the kubectl trace examples here.

For the submodules of this repository, we reference these branches accordingly, until (hopefully) all are merged and have a point release associated with them.

You also must have a kernel that supports all of the bpftrace/bcc features. To probe userspace containers on overlayfs, you need kernel 4.18 or later. A minimum of kernel 4.14 is needed for many examples here.

Motivation

I started this document with the hope that it would act as a helpful introduction to a number of cool new technologies being developed to enhance system observability on Linux platforms. With containerization being the dominant paradigm for production environments, workloads have moved from statically scheduled, orderly single-tenant deployments, to multi-tenant swarms of containers.

As a Production Systems Operator, eBPF has proven itself to be is a useful tool to help reliably give insight into deployed code serving live traffic where otherwise it would be difficult to see what an application is doing without compromising performance and bogging down the user experience of a live system, or worse, compromising and crashing it entirely.

The relative ease of writing language-specific bindings, even for dynamically evaluated languages, I think has bent the learning curve to the point that it is within reach, or has become a “lower hanging fruit” than it was before. While much work is ongoing for distributed tracing, I see this to be complementary to this type of userspace system tracing. Distributed tracing can show the interactions between apps, and USDT tracing and uprobes can help to drill down into individual systems.

I hope you enjoy reading this report and find the content accessible. I am constantly seeking to improve my writing and communication skills, so if you have suggestions please give me the gift of feedback on any suggestions to help improve accessibility and clarity.

-Dale Hamel

Introduction

USDT - Userspace Statically Defined Tracepoints

USDT tracepoints are a powerful tool that gained popularity with dtrace.

In short, USDT tracepoints allow you to build-in diagnostics at key points of an application.

These can be used for debugging the application, measuring the performance characteristics, or analyzing any aspect of the runtime state of the program.

USDT tracepoints are placed within your code, and are executed when:

- They have been explicitly enabled.

- A tracing program, such as

bpftraceordtraceis connected to it.

Portability

Originally limited to BSD, Solaris, and other systems with dtrace, it is now simple to use USDT tracepoints on Linux. systemtap for linux has produced sys/sdt.h that can be used to add dtrace probes to linux applications written in C, and for dynamic languages libstapsdt [1] can be used to add static tracepoints using whatever C extension framework is available for the language runtime. To date, there are wrappers for golang, Python, NodeJS, and a Ruby [2] wrapper under development.

bpftrace’s similarity to dtrace allows for USDT tracepoints to be accessible throughout the lifecycle of an application.

While more-and-more developers use Linux, there are still a large representation of Apple laptops for professional workstations. Many such enterprises also deploy production code to Linux systems. In such situations, developers can benefit from the insights that dtrace tracepoints have to offer them on their workstation as they are writing code. Once the code is ready to be shipped, the tracepoints can simply be left in the application. When it comes time to debug or analyze the code in production, the very same toolchain can be applied by translating dtrace’s .dt scripts into bpftrace’s `.bt scripts.

Broad use of such tracepoints should be encouraged, as there is no performance downside to leaving them in the application. The greater the number of well-placed tracepoints in an application, the more tools developers will have at their disposal to gain insight into their application’s real-world runtime characteristics.

Performance

Critically, USDT tracepoints have little to no impact on performance if they are not actively being used.

This is what sets aside USDT tracepoints from other diagnostic tools, such as emitting metrics through statsd or writing to a logger.

This makes USDT tracepoints great to deploy surgically, rather than the conventional “always on” diagnostics. Logging data and emitting metrics do have some runtime overhead, and it is constant. The overhead that USDT tracepoints have is minimal, and limited to when they are actively being used to help answer a question about the behavior of an application.

bpftrace

bpftrace [3] is an emerging new tool that is based on eBPF support added to version 4.1 of the linux kernel. While rapidly under development, it already supports much of dtrace’s functionality.

You can use bpftrace in production systems to attach to and summarize data from trace points similarly to with dtrace.

For more details for bpftrace, check out its own reference guide [4] and this great article [5].

You can bpftrace programs by specifying a string with the -e flag, or by running a bpftrace script (conventionally ending in .bt) directly.

Tracing Examples

For most examples, we’ll assume you have two terminals side-by-side:

- One to run the program you want to trace (referred to as tracee).

- One to run your bpftrace and observe the output.

Note that for development cases on OS X, dtrace usage is covered elsewhere.

The source and all of these scripts are available in the examples folder of this repository, or from submodules.

Listing tracepoints

To list tracepoints that you can trace:

bpftrace -l 'usdt:*' -p ${PROCESS}Simple hello world

# frozen_string_literal: true

require 'ruby-static-tracing'

t = StaticTracing::Tracepoint.new('global', 'hello_world',

Integer, String)

t.provider.enable

loop do

if t.enabled?

t.fire(StaticTracing.nsec, 'Hello world')

puts 'Probe fired!'

else

puts 'Not enabled'

end

sleep 1

endThis is a basic ruby script that demonstrates the basic use of static tracepoints in Ruby, usin the library ruby-static-tracing [2] Ruby gem, covered later.

This simplistic program will loop indefinitely, printing Not Enabled every second. This represents the Ruby program going on it’s merry way, doing what it’s supposed to be doing - pretend that it is running actual application code. The application isn’t spending any time executing probes, all it is doing is checking if the probe is enabled. Since the probe isn’t enabled, it continues with business as usual. The cost of checking if a probe is enabled is extraordinarily low, ~5 micro seconds).

This example:

- Creates a provider implicitly through it’s reference to ‘global’, and indicates that it will be firing off an Integer and a String to the tracepoint.

- Registering the tracepoint is like a function declaration - when you fire the tracepoint later, the fire call must match the signature declared by the tracepoint.

- We fetch the the provider that we created, and enable it.

- Enabling the provider loads it into memory, but the tracepoint isn’t enabled until it’s attached to.

Then, in an infinite loop, we check to see if our tracepoint is enabled, and fire it if it is.

When we run helloworld.rb, it will loop and print:

Not enabled

Not enabled

Not enabledOne line about every second. Not very interesting, right?

When we run our tracing program though:

bpftrace -e 'usdt::global:hello_nsec

{ printf("%lld %s\n", arg0, str(arg1))}' -p $(pgrep -f helloworld.rb)Or, using a script:

bpftrace ./helloworld.bt -p $(pgrep -f helloworld.rb)helloworld.bt:

We’ll notice that the output changes to indicate that the probe has been fired:

Not enabled

Probe fired!

Probe fired!

Probe fired!And, from our bpftrace process we see:

Attaching 1 probe...

55369896776138 Hello world

55370897337512 Hello world

55371897691043 Hello worldUpon interrupting our bpftrace with Control+C, the probe stops firing as it is no longer enabled.

This demonstrates:

- How to get data from ruby into our bpftrace using a tracepoint.

- That probes are only enabled when they are attached to.

- How to read integer and string arguments.

- Basic usage of bpftrace with this gem.

In subsequent examples, none of these concepts are covered again.

Aggregation functions

While the hello world sample above is powerful for debugging, it’s basically just a log statement.

To do something a little more interesting, we can use an aggregation function.

bpftrace can generate linear and log2 histograms on map data. Linear histograms show the same data that is used to construct an ApDex[6]. This type of tracing is good for problems like understanding request latency.

For this example, we’ll use randist.rb to analyze a pseudo-random distribution of data.

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

require 'ruby-static-tracing'

t = StaticTracing::Tracepoint.new('global', 'randist', Integer)

t.provider.enable

r = Random.new

loop do

t.fire(r.rand(100))

endThe example should fire out random integers between 0 and 100. We’ll see how random it actually is with a linear histogram, bucketing the results into steps of 10:

bpftrace -e 'usdt::global:randist

{@ = lhist(arg0, 0, 100, 10)}' -p $(pgrep -f ./randist.rb)

Attaching 1 probe...@:

[0, 10) 817142 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[10, 20) 815076 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[20, 30) 815205 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[30, 40) 814752 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[40, 50) 815183 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[50, 60) 816676 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[60, 70) 816470 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[70, 80) 815448 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[80, 90) 816913 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[90, 100) 814970 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

There are similar aggregation functions [4] for max, mean, count, etc that can be used to summarize large data sets - check them out!

Latency distributions

This example will profile the function call that we use for getting the current monotonic time in nanoseconds:

StaticTracing.nsecUnder the hood, this is just calling a libc function to get the current time against a monotonic source. This is how we calculate the latency in wall-clock time. Since we will be potentially running this quite a lot, we want it to be fast!

For this example, we’ll use nsec.rb script to compute the latency of this call and fire it off in a probe.

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

require 'ruby-static-tracing'

t = StaticTracing::Tracepoint.new('global', 'nsec_latency', Integer)

t.provider.enable

loop do

s = StaticTracing.nsec

StaticTracing.nsec

f = StaticTracing.nsec

t.fire(f-s)

sleep 0.001

endAttaching to it with a log2 histogram, we can see that it clusters within a particular latency range:

bpftrace -e 'usdt::global:nsec_latency

{@ = hist(arg0)}' -p $(pgrep -f ./nsec.rb)

Attaching 1 probe...@:

[256, 512) 65 | |

[512, 1K) 162 |@@ |

[1K, 2K) 3647 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[2K, 4K) 3250 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[4K, 8K) 6 | |

[8K, 16K) 0 | |

[16K, 32K) 12 | |

[32K, 64K) 2 | |

Let’s zoom in on that with a linear histogram to get a better idea of the latency distribution:

bpftrace -e 'usdt::global:nsec_latency

{@ = lhist(arg0, 0, 3000, 100)}' -p $(pgrep -f ./nsec.rb)

Attaching 1 probe...@:

[300, 400) 1 | |

[400, 500) 33 |@ |

[500, 600) 50 |@@ |

[600, 700) 49 |@@ |

[700, 800) 42 |@@ |

[800, 900) 21 |@ |

[900, 1000) 15 | |

[1000, 1100) 9 | |

[1100, 1200) 11 | |

[1200, 1300) 4 | |

[1300, 1400) 16 | |

[1400, 1500) 9 | |

[1500, 1600) 7 | |

[1600, 1700) 8 | |

[1700, 1800) 70 |@@@ |

[1800, 1900) 419 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1900, 2000) 997 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[2000, 2100) 564 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[2100, 2200) 98 |@@@@@ |

[2200, 2300) 37 |@ |

[2300, 2400) 30 |@ |

[2400, 2500) 36 |@ |

[2500, 2600) 46 |@@ |

[2600, 2700) 86 |@@@@ |

[2700, 2800) 74 |@@@ |

[2800, 2900) 42 |@@ |

[2900, 3000) 26 |@ |

[3000, ...) 35 |@ |

We can see that most of the calls are happening within 1700-2200 nanoseconds, which is pretty blazing fast, around 1-2 microseconds. Some are faster, and some are slower, representing the long-tails of this distribution, but this can give us confidence that this call will complete quickly.

Adding USDT support to a dynamic language

ruby-static-tracing

While USDT tracepoints are conventionally defined in C and C++ applications with a preprocessor macro, systemtap has created their own library for sdt tracepoints, which implement the same API as dtrace, on Linux. A wrapper around this, libstapsdt[1] is used to generate and load tracepoints in a way that can be used in dynamic languages like Ruby.

ruby-static-tracing is a gem that demonstrates the powerful applications of USDT tracepoints. It wraps libstapsdt for Linux support, and libusdt for Darwin / OS X support. This allows the gem to expose the same public Ruby api, implemented against separate libraries with specific system support. Both of these libraries are vendored-in, and dynamically linked via RPATH modifications. On Linux, libelf is needed to build and run libstapsdt, on Darwin, libusdt is built as a dylib and loaded alongside the ruby_static_tracing.so app bundle.

ruby-static-tracing implements wrappers for libstapsdt through C extensions. The scaffold / general design of ruby-static-tracing is based on the semian gem, and in the same way that Semian supports helpers to make it easier to use, we hope to mimic and take inspiration many of the same patterns to create tracers. Credit to the Semian authors Scott Francis [7] and Simon Hørup Eskildsen [8] for this design as starting point.

In creating a tracepoint, we are calling the C code:

VALUE

tracepoint_initialize(VALUE self, VALUE provider, VALUE name, VALUE vargs) {

VALUE cStaticTracing, cProvider, cProviderInst;

static_tracing_tracepoint_t *tracepoint = NULL;

const char *c_name_str = NULL;

int argc = 0;

c_name_str = check_name_arg(name);

check_provider_arg(provider); // FIXME should only accept string

Tracepoint_arg_types *args = check_vargs(&argc, vargs);

/// Get a handle to global provider list for lookup

cStaticTracing = rb_const_get(rb_cObject, rb_intern("StaticTracing"));

cProvider = rb_const_get(cStaticTracing, rb_intern("Provider"));

cProviderInst = rb_funcall(cProvider, rb_intern("register"), 1, provider);

// Use the provider to register a tracepoint

SDTProbe_t *probe =

provider_add_tracepoint_internal(cProviderInst, c_name_str, argc, args);

TypedData_Get_Struct(self, static_tracing_tracepoint_t,

&static_tracing_tracepoint_type, tracepoint);

// Stare the tracepoint handle in our struct

tracepoint->sdt_tracepoint = probe;

tracepoint->args = args;

return self;

}You can see that the tracepoint will register a provider for itself if it hasn’t happened already, allowing for “implicit declarations” of providers on their first reference.

And in firing a tracepoint, we’re just wrapping the call in libstapsdt:

case 1:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0]);

break;

case 2:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0], args[1]);

break;

case 3:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0], args[1], args[2]);

break;

case 4:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0], args[1], args[2], args[3]);

break;

case 5:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0], args[1], args[2], args[3], args[4]);

break;

case 6:

probeFire(res->sdt_tracepoint, args[0], args[1], args[2], args[3], args[4],

args[5]);and the same for checking if a probe is enabled:

VALUE

tracepoint_enabled(VALUE self) {

static_tracing_tracepoint_t *res = NULL;

TypedData_Get_Struct(self, static_tracing_tracepoint_t,

&static_tracing_tracepoint_type, res);

return probeIsEnabled(res->sdt_tracepoint) == 1 ? Qtrue : Qfalse;

}In general, all of the direct provider and tracepoint functions are called directly through these C-extensions, wrapping around libstapsdt [1].

So to understand what happens when we call a tracepoint, we will need to dive into how libstapsdt works, to explain how we’re able to probe Ruby from the kernel.

libstapsdt

This library was written by Matheus Marchini [9] and Willian Gaspar [10], and provides a means of generating elf notes in a format compatible to DTRACE macros for generating elf notes on linux.

For each provider declared, libstapsdt will create an ELF file that can be loaded directly into ruby’s address space through dlopen. As a compiler would normally embed these notes directly into a C program, libstapsdt matches this output format exactly. Once all of the tracepoints have been registered against a provider, it can be loaded into the ruby process’s address space through a dlopen call on a file descriptor for a temporary (or memory-backed) file containing the ELF notes.

For each tracepoint that we add to each provider, libstapsdt will inject assembly for the definition of a function called _funcStart. This function is defined in an assembly file. You might be cringing at the thought of working with assembly directly, but this definition is quite simple:

It simply inserts four NOP instructions, followed by a RET. In case you don’t speak assembly, this translates to instructions that say to “do nothing, and then return”.

The address of this blob of assembly is used as the address of the function probe._fire in libstapsdt. So, each probe is calling into a memory region that we’ve dynamically loaded into memory, and the addresses of these probes can be computed by reading the elf notes on these generated stubs.

To understand this better, we’ll dive into how libstapsdt works. This will take us all the way from the Ruby call, to down inside the kernel.

Examining the dynamically loaded ELF

For our ruby process with a loaded provider, we can see the provider in the address space of the process:

cat /proc/22205/maps | grep libstapsdt:global

7fc624c3b000-7fc624c3c000 r-xp [...] 9202140 /memfd:libstapsdt:global (deleted)

7fc624c3c000-7fc624e3b000 ---p [...] 9202140 /memfd:libstapsdt:global (deleted)

7fc624e3b000-7fc624e3c000 rw-p [...] 9202140 /memfd:libstapsdt:global (deleted)The left-most field is the process memory that is mapped to this library. Note that it appears 3 times, for the different permission modes of the memory (second column). The number in the center is the inode associated with our memory image, and it is identical for all of them because they are all backed by the same memory-only file descriptor. This is why, to the very right, we see (deleted) - the file descriptor doesn’t actually exist on the filesystem at the address specified.

This is because we are using a memory-backed file descriptor to store the ELF notes. The value shown here for /memfd:[...] is a special annotation for file descriptors that have no backing file and exist entirely in memory. We do this so that we don’t have to clean up the generated ELF files manually.

In examining the file descriptors for this process, we find that one of them matches the name and apparent path of this file memory mapped segment:

$ readlink -f /proc/22205/fd/*

/dev/pts/11

/dev/pts/11

/dev/pts/11

/proc/22205/fd/pipe:[9202138]

/proc/22205/fd/pipe:[9202138]

/proc/22205/fd/pipe:[9202139]

/proc/22205/fd/pipe:[9202139]

/memfd:libstapsdt:global (deleted)

/dev/null

/dev/nullIt happens to be at the path /proc/22205/fd/7. If we read our elf notes for this path, we get what we expect:

readelf --notes /proc/22205/fd/7

Displaying notes found in: .note.stapsdt

Owner Data size Description

stapsdt 0x00000039 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: global

Name: hello_nsec

Location: 0x0000000000000280, Base: 0x0000000000000340, Semaphore: 0x0000000000000000

Arguments: 8@%rdi -8@%rsi

stapsdt 0x0000002e NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: global

Name: enabled

Location: 0x0000000000000285, Base: 0x0000000000000340, Semaphore: 0x0000000000000000

Arguments: 8@%rdiAnd, if we just read the memory space directly using the addresses for our ELF blob earlier:

readelf --notes /proc/22205/map_files/7fc624c3b000-7fc624c3c000

Displaying notes found in: .note.stapsdt

Owner Data size Description

stapsdt 0x00000039 NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: global

Name: hello_nsec

Location: 0x0000000000000280, Base: 0x0000000000000340, Semaphore: 0x0000000000000000

Arguments: 8@%rdi -8@%rsi

stapsdt 0x0000002e NT_STAPSDT (SystemTap probe descriptors)

Provider: global

Name: enabled

Location: 0x0000000000000285, Base: 0x0000000000000340, Semaphore: 0x0000000000000000

Arguments: 8@%rdiWe see that it matches exactly!

Notice that the location of global:hello_nsec is 0x0280 in the elf notes.

Now we will use gdb to dump the memory for our program so that we can examine the hexadecimal of its address space.

sudo gdb --pid 22205

(gdb) dump memory unattached 0x7fc624c3b000 0x7fc624c3c000hexdump -C unattached00000230 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 10 00 07 00 |................|

00000240 20 01 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | . .............|

00000250 00 5f 5f 62 73 73 5f 73 74 61 72 74 00 5f 65 64 |.__bss_start._ed|

00000260 61 74 61 00 5f 65 6e 64 00 65 6e 61 62 6c 65 64 |ata._end.enabled|

00000270 00 68 65 6c 6c 6f 5f 6e 73 65 63 00 00 00 00 00 |.hello_nsec.....|

00000280 90 90 90 90 c3 90 90 90 90 c3 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000290 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 78 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........x.......|

000002a0 05 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........P.......|

000002b0 06 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 a8 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000002c0 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........,.......|Lets take a closer look at that address 0x280:

Those first 5 bytes look familiar! Recall the definition of _funcStart earlier:

The assembly instruction NOP corresponds to 0x90 on x86 platforms, and the assembly instruction RET corresponds to 0xc3. So, we’re looking at the machine code for the stub function that we created with libstapsdt. This is the code that will be executed every time we call fire in userspace. The processor will run four NOP instructions, and then return.

As we can see in libstapsdt, the address of probe._fire is set from the location of the probe’s name, as calculated from the ELF offset:

for(SDTProbeList_t *node=provider->probes; node != NULL; node = node->next) {

fireProbe = dlsym(provider->_handle, node->probe.name);

// TODO (mmarchini) handle errors better when a symbol fails to load

if ((error = dlerror()) != NULL) {

sdtSetError(provider, sharedLibraryOpenError, provider->_filename,

node->probe.name, error);

return -1;

}

node->probe._fire = fireProbe;

}So this is what the memory space looks like where we’ve loaded our ELF stubs, and we can see how userspace libstapsdt operations work.

For instance, the code that checks if a provider is enabled:

int probeIsEnabled(SDTProbe_t *probe) {

if(probe->_fire == NULL) {

return 0;

}

if(((*(char *)probe->_fire) & 0x90) == 0x90) {

return 0;

}

return 1;

}It is simply checking the memoryspace to see if the address of the function starts with a NOP instruction (0x90).

Now, if we attach to our program with bpftrace, we’ll see the effect that attaching a uprobe to this address will have.

Dumping the same memory again with gdb:

00000230 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 14 00 00 00 10 00 07 00 |................|

00000240 20 01 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | . .............|

00000250 00 5f 5f 62 73 73 5f 73 74 61 72 74 00 5f 65 64 |.__bss_start._ed|

00000260 61 74 61 00 5f 65 6e 64 00 65 6e 61 62 6c 65 64 |ata._end.enabled|

00000270 00 68 65 6c 6c 6f 5f 6e 73 65 63 00 00 00 00 00 |.hello_nsec.....|

00000280 cc 90 90 90 c3 90 90 90 90 c3 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000290 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 78 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........x.......|

000002a0 05 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 50 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........P.......|

000002b0 06 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 a8 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000002c0 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........,.......|We see that the first byte of our function has changed!

Where we previously had a function that did NOP NOP NOP NOP RET, we now have the new instruction 0xCC, which on x86 platforms is the “breakpoint” instruction known as int3.

When our enabled check runs now, it will see that the bytes at the start of the function are not a NOP, and are INT3 instead. Now that our function is enabled, our code will allow us to call probe._fire.

We can pass up to 6 arguments when firing the probe. The code in libstapsdt simply passes every possibly arg count from a variadic list signature using a switch statement:

switch(probe->argCount) {

case 0:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) ();

return;

case 1:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0]);

return;

case 2:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0], arg[1]);

return;

case 3:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0], arg[1], arg[2]);

return;

case 4:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0], arg[1], arg[2], arg[3]);

return;

case 5:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0], arg[1], arg[2], arg[3], arg[4]);

return;

case 6:

((void (*)())probe->_fire) (arg[0], arg[1], arg[2], arg[3], arg[4], arg[5]);

return;When the address is called, the arguments passed in will be pushed onto the stack for this function call. This is how our probe is able to read arguments - by examining the address space of the caller’s stack.

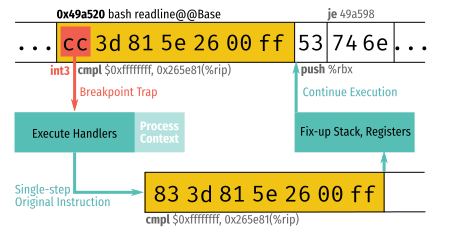

int3 (0xCC), NOP (0x90) and uprobes

When the probe is fired, the kernel begins its trap handler. We can see this by running a trace of the kernel’s trap handler while we attach our probe:

$ bpftrace -e 'kprobe:is_trap_insn { printf("%s\n", kstack) }'

Attaching 1 probe...

is_trap_insn+1

install_breakpoint.isra.12+546

register_for_each_vma+792

uprobe_apply+109

trace_uprobe_register+429

perf_trace_event_init+95

perf_uprobe_init+189

perf_uprobe_event_init+65

perf_try_init_event+165

perf_event_alloc+1539

__se_sys_perf_event_open+401

do_syscall_64+90

entry_SYSCALL_64_after_hwframe+73We can see that attaching the uprobe via the perf event is what causes the probe to be enabled, and this is visible to the userspace process.

When an enabled probe is fired, the trap handler is called.

int3 is a special debugging/breakpoint instruction with opcode 0xCC. When a uprobe is enabled, it will overwrite the memory at the probe point with this single-byte instruction, and save the original byte for when execution is resumed. Upon executing this instruction, the uprobe is triggered and the handle routine is executed. Upon completion of the handler routine, the original assembly is executed.

As we showed above, the address where we place the uprobe is actually in the mapped address space of the generated ELF binary, and a NOP instruction (0x90) is all we are overwriting.

So, in order to check if a tracepoint is enabled, we just check the address of our tracepoint to see if it contains a NOP instruction. If it does, then the tracepoint isn’t enabled. If it doesn’t, then a uprobe has placed a 0xCC instruction here, and we know to execute our tracepoint logic.

Upon firing the probe, libstapsdt will actually execute the code at this address, letting the kernel “take the wheel” briefly, to collect the trace data. This will execute our eBPF program that collects the tracepoint data and buffers it inside the kernel, then hand control back to our userspace ruby process.

Diagram credit [11].

USDT read arguments

Here we can see how arguments are pulled off the stack by bpftrace.

Its call to bcc’s bcc_usdt_get_argument builds up an argument struct:

argument->size = arg.arg_size();

argument->valid = BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_NONE;

if (arg.constant()) {

argument->valid |= BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_CONSTANT;

argument->constant = *(arg.constant());

}

if (arg.deref_offset()) {

argument->valid |= BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_DEREF_OFFSET;

argument->deref_offset = *(arg.deref_offset());

}

if (arg.deref_ident()) {

argument->valid |= BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_DEREF_IDENT;

argument->deref_ident = arg.deref_ident()->c_str();

}

if (arg.base_register_name()) {

argument->valid |= BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_BASE_REGISTER_NAME;

argument->base_register_name = arg.base_register_name()->c_str();

}

if (arg.index_register_name()) {

argument->valid |= BCC_USDT_ARGUMENT_INDEX_REGISTER_NAME;

argument->index_register_name = arg.index_register_name()->c_str();

}These functions are implemented using platform-specific assembly to read the arguments off of the stack.

We can see that the special format string for the argument in the ELF notes, eg 8@%rdi, is parsed to determine the address to read the argument from:

ssize_t ArgumentParser_x64::parse_expr(ssize_t pos, Argument *dest) {

if (arg_[pos] == '$')

return parse_number(pos + 1, &dest->constant_);

if (arg_[pos] == '%')

return parse_base_register(pos, dest);

if (isdigit(arg_[pos]) || arg_[pos] == '-') {

pos = parse_number(pos, &dest->deref_offset_);

if (arg_[pos] == '+') {

pos = parse_identifier(pos + 1, &dest->deref_ident_);

if (!dest->deref_ident_)

return -pos;

}

} else {

dest->deref_offset_ = 0;

pos = parse_identifier(pos, &dest->deref_ident_);

if (arg_[pos] == '+' || arg_[pos] == '-') {

pos = parse_number(pos, &dest->deref_offset_);

}

}This how each platform is able to parse out the argument notation, to know where and how to pull the data out of the callstack.

USDT tracing in rails

A sample app [12] is used to explain the usage of tracers from ruby-static-tracing in Rails. This functionality was developed during a Hackdays event, with credit to Derek Stride [13], Matt Valentine-House [14], and Gustavo Caso [15].

We can add ruby-static-tracing [2] to our rails enabling tracers in our application config:

require 'ruby-static-tracing'

require 'ruby-static-tracing/tracer/concerns/latency_tracer'

StaticTracing.configure do |config|

config.add_tracer(StaticTracing::Tracer::Latency)

end

# Require the gems listed in Gemfile, including any gems

# you've limited to :test, :development, or :production.

Bundler.require(*Rails.groups)

module UsdtRails

class Application < Rails::Application

# Initialize configuration defaults for originally generated Rails version.

config.load_defaults 5.2

config.after_initialize { eager_load! }Then, for the controller we want to trace we just need to include our latency tracer:

class SampleController < ApplicationController

def all

1000.times do

([] << 1) * 100_000

end

end

def welcome

100.times do

([] << 1) * 100_000

end

end

def slow

sleep(rand(0.5..1.5))

end

def random

sleep(rand(0..0.9))

end

include StaticTracing::Tracer::Concerns::Latency

endWhen we start up our app, we don’t actually see the tracepoints we’re looking for because they aren’t enabled by default. The following returns nothing:

$ bpftrace -l 'usdt:*:sample_controller:*' -p 10954But, if we enable it with SIGPROF:

We now see some output:

$ bpftrace -l 'usdt:*:sample_controller:*' -p 10954

usdt:/proc/10954/fd/21:sample_controller:random

usdt:/proc/10954/fd/21:sample_controller:welcome

usdt:/proc/10954/fd/21:sample_controller:slow

usdt:/proc/10954/fd/21:sample_controller:allSo we’ll attach to each of these, and print a histogram of the latency for each:

$ bpftrace -e 'usdt::sample_controller:*

{ @[str(arg0)] = lhist(arg1/1000000, 0, 2000, 100); }' -p 10954

Attaching 4 probes...While the bpftrace is running, we’ll send some work to our sample app. We’ll fire up a script [16] to generate some traffic using wrk to each of the paths on this controller:

#!/bin/bash

CONNS=500

THREADS=500

DURATION=60

wrk -c${CONNS} -t${THREADS} -d${DURATION}s -s ./multi-request-json.lua http://127.0.0.1:3000Once our traffic generation script exits, we’ll interrupt bpftrace from earlier to signal it to print and summarize the data it collected:

@[all]:

[100, 200) 18 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[200, 300) 54 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[300, 400) 1 | |

@[welcome]:

[0, 100) 73 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

@[random]:

[0, 100) 4 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[100, 200) 11 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[200, 300) 10 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[300, 400) 5 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[400, 500) 8 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[500, 600) 9 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[600, 700) 8 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[700, 800) 13 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[800, 900) 5 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[900, 1000) 1 |@@@@ |

@[slow]:

[500, 600) 8 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[600, 700) 12 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@|

[700, 800) 5 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[800, 900) 8 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[900, 1000) 10 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1000, 1100) 7 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1100, 1200) 6 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1200, 1300) 6 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1300, 1400) 3 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1400, 1500) 6 |@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ |

[1500, 1600) 1 |@@@@ |

[1600, 1700) 2 |@@@@@@@@ |We can see the latency distribution, and the count of each request that fell into each bucket in the histogram.

This results line up with what wrk reports in its summary, and the request data that is logged by the rails console.

USDT examples in other dynamic languages

To demonstrate the portability of these same concepts, language-specific examples are provided here.

We will implement the same hello-word style of probe of each of them, and explain the differences and implementation of each language.

Ruby wrapper (featured elsewhere)

Above ruby-static-tracing[2] is featured more and examined heavily featured than other language runtimes, to illustrate the approach of adding libstapsdt to a dynamic runtime. Most of these same concepts apply to other languages.

For example, the Rails usage concept of tracers may be portable to Django. In the same way that ruby-static-tracing offers an abstraction above tracepoints, other runtimes could take similar approaches.

Ruby won’t be repeated here, and it is the author’s [17] bias and ignorance that Ruby is featured more heavily throughout the rest of the report.

If you have examples of more detailed uses of each of USDT tracepoints in any other languages missing here, please submit a pull request.

Python wrapper

To illustrate the point, we’ll how we’re able to add static tracepoints to python, which is similar to what we’ll be doing here with ruby.

Examining the python wrapper [9], we can see a sample probe program:

from time import sleep

import stapsdt

provider = stapsdt.Provider("pythonapp")

probe = provider.add_probe(

"firstProbe", stapsdt.ArgTypes.uint64, stapsdt.ArgTypes.int32)

provider.load()

while True:

print("Firing probe...")

if probe.fire("My little probe", 42):

print("Probe fired!")

sleep(1)NodeJS wrapper

A similar example, in nodejs [9], a similar sample probe:

const USDT = require("usdt");

const provider = new USDT.USDTProvider("nodeProvider");

const probe1 = provider.addProbe("firstProbe", "int", "char *");

provider.enable();

let countdown = 10;

function waiter() {

console.log("Firing probe...");

if(countdown <= 0) {

console.log("Disable provider");

provider.disable();

}

probe1.fire(function() {

console.log("Probe fired!");

countdown = countdown - 1;

return [countdown, "My little string"];

});

}

setInterval(waiter, 750);golang wrapper

For golang, our example comes from salp [18]:

var (

probes = salp.NewProvider("salp-demo")

p1 = salp.MustAddProbe(probes, "p1", salp.Int32, salp.Error, salp.String)

p2 = salp.MustAddProbe(probes, "p2", salp.Uint8, salp.Bool)

)libusdt

ruby-static-tracing [2] also wraps libusdt for Darwin / OSX support.

libusdt is the provider used for dtrace probes and many of the examples powering the libraries on [19]

// FIXME do an analysis of the similarities of libusdt and libstapsdt, DOF vs ELF approach

// Explain how libusdt is wrapped on Darwin

kubectl-trace

// FIXME add citation for kubectl-trace crew

For production applications, kubectl-trace offers a convenient way to tap into our USDT tracepoints in production.

kubectl-trace will create a new kubernetes job, with a pod that runs bpftrace with the arguments provided by the user.

We can use kubectl-trace to apply a local bpftrace script or expression to bpftrace instance running alongside our application. This allows for very easy, targetted tracing in production.

// FIXME have an example of tracing a web app

Use in Local Development Environments

Using virtualization

If your development environment already runs on top of a hypervisor, such as Docker for Mac or Docker for Windows. However, at present these do not currently work with bpftrace, as the kernel is too old and doesn’t support the necessary features. You can (and I have) built an updated kernel using linuxkit [20], but while this does work it breaks the filesharing protocols used for bind-mounting with at least Docker for Mac.

If WSL comes with a new enough kernel or can load custom kernels, it may be able to play a similar role to xhyve [21] or hyperkit [22], but I have not tested against a Windows development environment or WSL.

Vagrant is another option, and a Vagrantfile is included as a reference implementation for how to bootstrap a minimal-enough VM to get the included Dockerfile to run.

The long and short of this approach is that it is good for if you are running your development application or dependencies inside of a linux VM, they can be traced with bpftrace provided that the kernel is new enough.

dtrace

Some environments may use a Linux VM, such as Docker for Mac, Docker For Windows, or Railgun [23], but run the actual application on the host OS, to provide a more native development experience.

In these cases, since the application isn’t running inside of Linux, they cannot be probed with bpftrace. Luckily, OS X and Darwin include dtrace, and it can be used out-of-the-box, for all of the functionality outlined here. For the discussion here, the focus will be mostly on dtrace on OS X.

When you run dtrace, it will complain about system integrity protection (SIP), which is an important security feature of OS X. Luckily, it doesn’t get in the way of how we implement probes here so the warning can be ignored.

You do, still, need to run dtrace as root, so have your sudo password ready or setuid the dtrace binary, as we do for our integration tests with a copy of the system dtrace binary.

dtrace can run commands specified by a string with the -n flag, or run script files (conventionally ending in .dt), with the -s flag.

[24]

Many simple dtrace scripts can be easily converted to bpftrace scripts see this cheatsheet [25], and vice-versa.

Listing tracepoints

To list tracepoints that you can trace:

On Darwin/OSX:

dtrace -l -P "${PROVIDER}${PID}"Simple hello world

Recall from earlier, when we run helloworld.rb, it will loop and print:

Not enabled

Not enabled

Not enabledOne line about every second. Not very interesting, right?

With dtrace:

dtrace -q -n 'global*:::hello_nsec

{ printf("%lld %s\n", arg0, copyinstr(arg1)) }'Or, with dtrace and a script:

dtrace -q -s helloworld.dthelloworld.dt:

Aggregation functions

dtrace has equivalent support to bpftrace for generating both linear and log2 histograms.

Recall from the example using randist.rb above:

The example should fire out random integers between 0 and 100. We’ll see how random it actually is with a linear histogram, bucketing the results into steps of 10:

dtrace -q -n 'global*:::randist { @ = lquantize(arg0, 0, 100, 10) }' value ------------- Distribution ------------- count

< 0 | 0

0 |@@@@ 145456

10 |@@@@ 145094

20 |@@@@ 145901

30 |@@@@ 145617

40 |@@@@ 145792

50 |@@@@ 145086

60 |@@@@ 146287

70 |@@@@ 146041

80 |@@@@ 145331

90 |@@@@ 145217

>= 100 | 0

There are other aggregation functions [26], similar to those offered by bpftrace.

Latency distributions

Recall the nsec example from earlier with bpftrace.

// FIXME add dtrace output for this example

Use in CI environments

// FIXME fill this out more

To use bpftrace and USDT in a linux CI environment, it will need to run as a Privileged container, or a container with near-root privileges.

This can be managed more safely if the bpftrace container is scoped back as much as possible.

One possible implementation would be to set up a bpftrace hook-points into the CI script, where bpftrace would be called to check output of a particular probe.

This would allow for sanity checking without the need for prints littered about.

Call stenography

Tools such as rotoscope [27] exist to trace method invocations in CI environments.

The built-in Ruby USDT probes can do this already, allowing for tracing of methods to be done outside of the ruby VM flow altogether.

A trivial bpftrace script can be written to log all method invocations in CI, and be used to help find dead code in CI.

Memory testing / analysis

Probes that use ObjectSpace can test for memory leaks by ensuring that unused objects are cleaned up when GC is called, and to try and catch objects that may never be released.

Integration testing

Integration tests can use bpftrace to verify that logic is executed, check expected parameters,

Performance testing

profile against a synthetic workloads test to prevent against AppDex [6] regressions, in CI or Production

Self-analysis

Using bpftrace, we can approximate the overhead of getting the current monotonic time. By examining the C code in ruby, we can see that Process.clock_gettime(Process::CLOCK_MONOTONIC) is merely a wrapper around the libc function clock_gettime.

Attaching to a Pry process and calling this function, we can get the nanosecond latency of obtaining this timing value from libc:

bpftrace -e 'uprobe:/lib64/libc.so.6:clock_gettime /pid == 16138/

{ @start[tid] = nsecs }

uretprobe:/lib64/libc.so.6:clock_gettime /@start [tid]

{

$latns = (nsecs - @start[tid]);

printf("%d\n", $latns);

delete(@start[tid]);

}'

Attaching 2 probes...

11853

5381

5440

4624

3263These are nanosecond values, which correspond to values between 0.005381 and 0.011853 ms. So, getting the before and after time adds on the order of about one hundredth of a millisecond of time spend in the thread.

This means that it would take about one hundred probed methods to add one millisecond to a service an application request. If requests are close to 100ms to begin with, this should make the overhead of tracing nearly negligible.

we must also measure the speed of checking if a probe is enabled to get the full picture, as well as any other in-line logic that is performed.

Future Work

More tracers for ruby-static-tracing

We’d like to see more tracers in ruby-static-tracing, and hopefully user-contributed ones as well.

There is potential for exploration of other aspects of ruby internals through USDT probes as well, such as ObjectSpace insights.

Through parsing headers, you may be able to use ruby-static-tracing to augment distributed traces, if you can hook up to the right span.

Kernel vs userspace buffering

It may not end up being an issue, but if probes are enabled (and fired!) persistently and frequently, the cost of the int3 trap overhead may become significant.

uprobes allow for buffering trace event data in kernel space, but lttng-ust provides a means to buffer data in userspace [28]. This eliminates the necessity of the int3 trap, and allows for buffering trace data in the userspace application rather than the kernel. This approach could be used to aggregate events and perform fewer trap interrupts, draining the userland buffers during each eBPF read-routine.

While lttng-ust does support userspace tracing of C programs already [29], in a way analogously to sys/sdt.h, there is no solution for a dynamic version an lttng-ust binary. Like DTRACE macros, the lttng-ust macros are used to build the handlers, and they are linked-in as a shared object. In the same way that libstapsdt builds elf notes, it’s possible that a generator for the shared library stub produced by lttng-ust could be built. A minimum proof of concept would be a JIT compiler that compiles a generated header into an elf binary that can be dlopen’d to map it into the tracee’s address space.

Analyzing the binary of a lttng-ust probe may give some clues as to how to build a minimal stub dynamically, as libstapsdt has done for systemtap’s dtrace macro implementation.

Implementing userspace support in libraries like ruby-static-tracing [2] by wrapping lttng-ust could also offer a means of using userspace tracepoints for kernels not supporting eBPF, and an interesting benchmark comparison of user vs kernel space tracing, perhaps offering complementary approaches [28].

ustack helpers in bpftrace

To have parity in debugging capabilities offered by dtrace, bpftrace needs to support the concept of a ustack helper.

As languages like nodejs have done, bpftrace and bcc should offer a means of reading annotations for JIT language instructions, mapping them back to the source code that generated the JIT instruction. Examining the approach that Nodejs and Python have taken to add support for ustack helpers, we should be able to generalize a means for bpftrace programs to interpret annotations for JIT instructions. [30]

Ruby JIT notes

Although ruby has a JIT under development [31], it would be ideal to have the code to annotate instructions for a ustack helper could be added now.

If ruby’s JIT simply wrote out notes in a way that would be easily loaded into a BPF map to notes by instruction, the eBPF probe can just check against this map for notes, and then the ustack helper in bpftrace would simply need a means of specifying how this map should be read when it is displayed.

This would allow for stacktraces that span ruby space (via the annotated JIT instructions), C methods (via normal ELF parsing), and the kernel itself. Hopefully offering similar functionality to what has been provided to nodejs [32].

While not actually related to directly USDT, ustack helpers in bpftrace and support for a ruby ustack helper would be tremendously impactful at understanding the full execution profile of ruby programs.

Ruby JIT is experimental and possibly to enable with --jit flag in 2.6 and higher. Perhaps adding JIT notes in a conforming way early could help to increase visibility into JIT’d code? ## BTF support

For introspecting userspace applications, BTF [33] looks like it will be useful for deeper analysis of a variety of typed-objects.

This may also free bpftrace and bcc from the need fork kernel headers, if the kernel type information can be read directly from BPF maps. For userspace programs, they may need to be compiled with BTF type information available, or have this information generated and loaded elsewhere somehow. This would be useful for analyzing the C components of language runtimes, such tracing the internals of the ruby C runtime, or analyzing C/C++ based application servers or databases.

BTF support requires a kernel v4.18 or newer, and the raw BTF documentation is available in the kernel sources [34]. Few userspace tools exist for BTF yet, but once it is added into tools like libbcc and bpftrace, a whole new realm of possibilities for debugging and tracing applications is possible.

USDT tracing alternatives

What distinguishes USDT tracepoints from a variety of other profiling and debugging tools is that other tools are generally either:

- Sampling profilers

- Trace every method invocation

- Require interrupting / stopping the program

This approach to tracing uses the x86 breakpoint instruction (INT3 0xCC) to trigger a kernel trap handler that will hand off execution to an eBPF probe. This use of breakpoints - injected by the kernel into the application via the kernel uprobe API, gives us the ability to perform targeted debugging on production systems.

Rather than printing to a character device (such as a log), or emitting a UDP or TCP based metric, USDT probes fire a kernel trap-handler. This allows for the kernel to do the work of collecting the local state, and summarizing it in eBPF maps.

breakpoints are only executed when there is an eBPF program installed and registered to handle the breakpoint. If there is nothing registered to the breakpoint, it is not executed. The overhead of this is nanoseconds.

For this reason, USDT tracepoints should be safe for use in production. The surgical precision that they offer in targeting memory addresses within the ruby execution context, and low overhead, make them a powerful tool.

It is less for generating flamegraphs of an application as a whole, and more for drilling in deep on a particular area of code

ptrace API

gdb

gdb can be used to debug applications, but generally requires a lot of overhead

strace

process_vm_readv

rbspy https://rbspy.github.io/using-rbspy/

signaling

rbtrace https://github.com/tmm1/rbtrace/blob/master/ext/rbtrace.c * stackprof github [37] * rbtrace github [38]

Ruby

Tracing api

Most standard debuggers for ruby use ruby’s built-in tracing API. Ruby in fact already has DTRACE probes. What distinguishes ruby-static-tracing from these other approaches is that USDT tracepoints are compiled-in to the application. Ruby’s tracing API is an “all or nothing” approach, affecting the execution of every single method. With USDT tracing, trace data is collected at execution time when a tracing breakpoint instruction is executed.

- rotoscope [27]

Update: As of Ruby 2.6, it is now possible to do this thanks to [39]! You can see the official docs [40] for more details, but it’s currently a bit light as it’s a pretty new API.

Acknowledgments

This is a report is meant to summarize my own research and experiments in this area, but the experience and research that went into making it all possible bears mentioning.

- Brendan Gregg [41] for his contributions to improving the accessibility of tracing tools throughout the industry

- Alastair Robertson [42] for creating bpftrace, and personally for reviewing the PRs I’ve submitted and offering insightful feedback

- Matheus Marchini [9] for his contributions to USDT tracing and feedback in reviews

- Willian Gaspar [10] for his contributions to iovisor and works featured here

- Jon Haslam [43] for his assistance and feedback on pull requests for USDT functionality in bpftrace

- Teng Qin [44] for reviewing my BCC patches with laser eyes

- Yonghong Song [45] for reviewing my BCC patches with laser eyes

- Julia Evans [46] for her amazing zines on tracing, rendering advanced concepts in accessible and creative formats, and her technical contributions to the tracing community and rbspy

- Lorenzo Fontana [47] for his work on creating and promoting kubetl-trace

- Leo Di Donato [48] for his work feedback and and insights on pull requests

I’d also like to specifically extend appreciation to Facebook and Netflix’s Engineering staff working on tracing and kernel development, for their continued contributions and leadership in the field of Linux tracing and contributions to eBPF, as well as the entire iovisor group.

Works Researched

Some of these may have been cited or sourced indirectly, or were helpful in my own research and understanding whether I explicitly cited them or not.

If you’d like to learn more, check out these other resources:

- Hacking Linux USDT with ftrace [49]

- USDT for reliable Userspace event tracing [50]

- We just got a new super-power! Runtime USDT comes to Linux [51]

- Seeing is Believing: uprobes and int3 Instruction [11]

- Systemtap UST wiki [52]

- Systemtap uprobe documentation [53]

- Linux tracing systems & how they fit together [54]

- Full-system dynamic tracing on Linux using eBPF and bpftrace [5]

- Awesome Dtrace - A curated list of awesome DTrace books, articles, videos, tools and resources [19]

[1] M. Marchini and W. Gaspar, “libstapsdt repository.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/sthima/libstapsdt

[2] D. Hamel, “ruby-static-tracing gem.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/dalehamel/ruby-static-tracing

[3] “bpftrace github repository.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/iovisor/bpftrace

[4] “bpftrace reference guide.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/iovisor/bpftrace/blob/master/docs/reference_guide.md

[5] H. Lai, “Full-system dynamic tracing on Linux using eBPF and bpftrace.” [Online]. Available: https://www.joyfulbikeshedding.com/blog/2019-01-31-full-system-dynamic-tracing-on-linux-using-ebpf-and-bpftrace.html

[6] “AppDex Wikipedia entry.”.

[7] S. Francis, “Scott Francis Github.”.

[8] S. Eskildsen, “Simon Hørup Eskildsen.”.

[9] M. Marchini, “Matheus Marchini’s homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://mmarchini.me/

[10] W. Gaspar, “Willian Gaspar’s Github.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/williangaspar

[11] A. Kolganov, “Seeing is Believing - uprobes and int3 Instruction.” [Online]. Available: https://dev.framing.life/tracing/uprobes-and-int3-insn/

[12] D. Hamel, “Rails App with USDT tracing sample.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/dalehamel/usdt-rails-sample

[13] D. Stride, “Derek Stride’s Github.”.

[14] M. Valentine-House, “Matt Valentine-House’s Homepage.”.

[15] gustavo caso, “gustavo caso’s homepage.”.

[16] M. Czeraszkiewicz, “WRK the HTTP benchmarking tool - Advanced Example.” [Online]. Available: http://czerasz.com/2015/07/19/wrk-http-benchmarking-tool-example/

[17] D. Hamel, “Dale Hamel’s Homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://blog.srvthe.net

[18] M. McShane, “Matt McShane’s Homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://mattmcshane.com/

[19] A. Števko, “Awesome Dtrace - A curated list of awesome DTrace books, articles, videos, tools and resources.” [Online]. Available: https://awesome-dtrace.com/

[20] “Linuxkit github repository.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/linuxkit/linuxkit

[21] “Xhyve github repository.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/machyve/xhyve/blob/master/README.md

[22] “Hyperkit github repository.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/moby/hyperkit

[23] J. Nadeau, “Current Developer Environments at Shopify.” [Online]. Available: https://devproductivity.io/shopify-developer-environments-p2/index.html

[24] “Dtrace OS X manpage.” [Online]. Available: http://www.manpagez.com/man/1/dtrace/osx-10.12.6.php

[25] B. Gregg, “bpftrace (DTrace 2.0) for Linux 2018.” [Online]. Available: http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2018-10-08/dtrace-for-linux-2018.html

[26] “dtrace guide on aggregation functions.” [Online]. Available: http://dtrace.org/guide/chp-aggs.html

[27] J. Husain and D. Dylan Thacker-Smith, “rotoscope github repo.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/Shopify/rotoscope

[28] M. Desnoyers, “Using user-space tracepoints with BPF.” [Online]. Available: https://lwn.net/Articles/754868/

[29] M. Desnoyers, “lttng-ust manpage.” [Online]. Available: https://lttng.org/man/3/lttng-ust/v2.10/

[30] D. Pacheco, “Understanding DTrace ustack helpers.” [Online]. Available: https://www.joyent.com/blog/understanding-dtrace-ustack-helpers

[31] S. Skipper, “Ruby’s New JIT.” [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/square-corner-blog/rubys-new-jit-91a5c864dd10

[32] D. Pacheco, “Where does your Node program spend its time?” [Online]. Available: http://dtrace.org/blogs/dap/2012/01/05/where-does-your-node-program-spend-its-time/

[33] A. Nakryiko, “Enhancing the Linux kernel with BTF type information.” [Online]. Available: https://facebookmicrosites.github.io/bpf/blog/2018/11/14/btf-enhancement.html

[34] “Kernel BTF documentation.” [Online]. Available: https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/latest/bpf/index.html#bpf-type-format-btf

[35] J. Evans, J. Evans, K. Marhubi, and J. Johnson, “rbspy github pages.” [Online]. Available: https://rbspy.github.io/

[36] J. Evans, J. Evans, K. Marhubi, and J. Johnson, “rbspy vs stackprof.” [Online]. Available: https://rbspy.github.io/rbspy-vs-stackprof/

[37] A. Gupta, “stackprof github repo.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/tmm1/stackprof

[38] A. Gupta, “rbtrace github repo.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/tmm1/rbtrace

[39] “Ruby 2.6 adds method tracing.” [Online]. Available: https://bugs.ruby-lang.org/issues/15289

[40] “Ruby 2.6 Method Tracing Docs.” [Online]. Available: https://ruby-doc.org/core-2.6/TracePoint.html#method-i-enable

[41] B. Gregg, “Brendan Gregg’s homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://brendangregg.com

[42] A. Robertson, “Alastair Robertson’s Homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://ajor.co.uk/projects/

[43] J. Haslam, “Jon Haslam’s Github.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/tyroguru

[44] T. Qin, “Teng Qin’s Github.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/palmtenor

[45] Y. Song, “Yonghong Song’s Github.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/yonghong-song

[46] J. Evans, “Julia Evans’s homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://jvns.ca/

[47] L. Fontana, “Lorenzo Fontana’s Homepage.” [Online]. Available: https://fntlnz.wtf/

[48] L. Di Donato, “Leo Di Donato’s Github.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/leodido

[49] B. Gregg, “Hacking Linux USDT with ftrace.” [Online]. Available: https://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2015-07-03/hacking-linux-usdt-ftrace.html

[50] J. Fernandes, “USDT for reliable Userspace event tracing.” [Online]. Available: https://www.joelfernandes.org/linuxinternals/2018/02/10/usdt-notes.html

[51] M. Marchini, “We just got a new super-power! Runtime USDT comes to Linux.” [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/sthima-insights/we-just-got-a-new-super-power-runtime-usdt-comes-to-linux-814dc47e909f

[52] M. Mark Wielaard and F. Eigler, “UserSpaceProbeImplementation - Systemtap Wiki.” [Online]. Available: https://sourceware.org/systemtap/wiki/UserSpaceProbeImplementation

[53] J. Keniston, “User-Space Probes (Uprobes).” [Online]. Available: https://sourceware.org/git/gitweb.cgi?p=systemtap.git;a=blob;f=runtime/uprobes/uprobes.txt;h=edd524be022691498c7f38133b0e32192dcbb35f;hb=a2b182f549cf64427a474803f3c02286b8c1b5e1

[54] J. Evans, “Linux tracing systems & how they fit together.” [Online]. Available: https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/07/05/linux-tracing-systems/